To the occasional confusion of those less aquatinted with the traditions of the royal family, Queen Elizabeth II has two birthdays each year, her actual birthday in April, and an official birthday on 13th June. Initiated in the reign of King George II, in 1748, the official birthday was introduced in order to provide a summer-time date on which to publicly celebrate the monarch. George was a November baby and the British autumn is not always amenable to outdoor events.

With the full pageantry of mounted cavalry, marching soldiers and military bands, the official birthday is marked by Trooping the Colour: a ceremony well-attuned to signifying the aura of the monarchy, as well as a historic endurance through time, unshifted by the passage from one year to the next. Normally taking place down The Mall in central London, the particular strangeness of 2020 means that even Trooping the Colour has this year been reduced in scale and relocated to Windsor Castle.

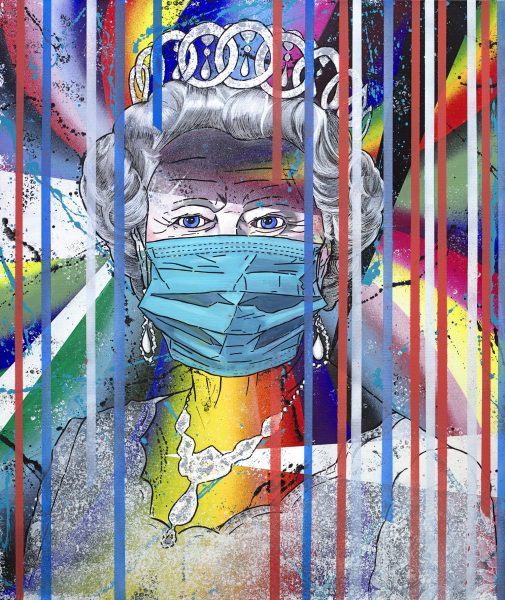

As the show goes on within the parameters of a global pandemic, The Net Gallery has marked the occasion by speaking to three artists who have depicted the Queen. The first two, Rupert Alexander and Stuart Brown, painted official portraits and share with us the process and experience involved in fulfilling such a prestigious commission. The third artist, Emelie Hryhoruk, provides a very current and timely perspective, having created an image that has grabbed media attention and succinctly illustrates the unprecedented impact of COVID-19.

‘HM The Queen’ by Rupert Alexander

Rupert Alexander is a painter who brings a sense of gravitas, but also intimacy to his portraits, capturing the humanity and individuality of his subjects. At the age of only 23, he had the rare opportunity to paint both the Duke of Edinburgh and the Price of Wales, before later painting the Queen herself:

The Net Gallery: Your connection with royal portraiture goes back a long way. How did that first invitation and opportunity arise, and how did that then lead to the portrait you made of the Queen?

Rupert Alexander: All three portraits were commissioned by the Royal Warrant Holders Association. The Association administers a scholarship called QEST (the Queen Elizabeth Scholarship Trust), one of which I won in 1995 to fund my first year of studies at The Florence Academy of Art. A couple of years later the Association commissioned me to paint the four members of the Royal Family who grant Royal Warrants (HM The Queen, HRH The Duke of Edinburgh, HRH The Prince of Wales and the Queen Mother). I painted the two princes shortly thereafter, and I was due to paint the Queen Mother at that time, but sadly didn’t get the opportunity to do so before she died. Sittings for the portrait of the Queen didn’t take place until nearly ten years later.

TNG: How did you find the experience of meeting and then painting the Queen as a subject, and did the interaction between you develop over the sittings?

RA: The three sittings with the Queen were wonderful. She was extremely kind and charming - and very funny. Because she has sat for so many portraits she had many interesting observations about other artists she had sat for over the years and we discussed my favourite portrait of her: Annigoni’s tempera and oil portrait from 1955.

TNG: Can you give a sense of how long each sitting took, and the process and materials you were using to produce your sketches?

RA: The sittings each lasted an hour, during which time I worked on a small oil study and took hundreds of photos. I find this is the best way of producing a portrait in an emergency: the colour sketch for the values and colour, and photos for the drawing. I then used all this material back in my studio to produce the full sized painting. In order that I could paint as much of the portrait from life as possible, I actually had a tailor make a copy of the Queen’s outfit and a wigmaker produce a wig resembling her hairstyle. I then used a stand-in model to paint it all from life.

Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II,

Air Commodore in Chief of the Royal Air Force Regiment, commissioned to mark the 75th anniversary of the formation of the Royal Air Force Regiment. By Stuart Brown.

With a background in illustration and commercial design, Stuart Brown has developed his practice to focus on oil paintings depicting military subject matter. Providing both intricate detail, and a palpable sense of place and events, his paintings illustrate battle scenes, as well as quieter moments in campaigns, and parades on home soil. The quality of Brown’s military work ultimately led to an official invitation to portray the commander-in-chief of the British Armed Forces:

“The portrait was commissioned by the Royal Air Force Regiment to mark their 75th Anniversary. I had previously completed commissions of combat scenes for the Regiment and it was obviously a great honour to be selected.

“The sitting took place in the White Drawing Room at Windsor Castle. The Queen is Air Commodore in Chief of the RAF Regiment and I hoped to capture something of her strong sense of duty, portraying the Queen working at a writing table.

“I worked with a limited ‘Zorn palette’ of Cadmium Red, Yellow Ochre, a cool Black and Titanium White. I find the limited palette helps keep the colour harmonious, while concentrating more on the composition and tonal pattern.

“The finished painting was presented to the Queen in 2018 and now hangs in the Officers’ Mess at RAF Honington, Suffolk.” Stuart Brown

‘We Will Meet Again’ by Emelie Hryhoruk

While the Queen stands for many as a personal symbol of stability and longevity, matching the historical sense of the monarchy as a deeply rooted institution, recent events have shaken even the most steadfast norms. The Queen herself has acknowledged the uniqueness of the times we have been living through, making a rare public address on 5th April. Inspired to respond, Wiltshire-based artist Emelie Hryhoruk produced an image that neatly captures the idea of the Queen in a time of lockdown, or rather one that encapsulates the era of lockdown by depicting one of our most recognisable figure heads. While the humble face mask has suddenly emerged as something we all now resonate with, the connection to Hryhoruk’s work is more pointed:

The Net Gallery: You’re known for depicting powerful figures, often fictional superheroes. How did the idea to paint the Queen arise, and did you plan to include the mask from the start, or was it something that you thought of as the portrait developed?

Emelie Hryhoruk: When Queen Elizabeth ll gave her broadcast in April, my attention was captured; I was compelled to mark her speech through art and, in turn, use my work to raise awareness and funds for the Mental Health charities I support.

Initially, I was leaning towards creating a portrait of an NHS worker or someone in a carers role wearing a face mask on the already prepped linen (I had been prepping the canvas for a Spiderman-inspired painting in previous weeks). I have learned many times, however, that life as a creative can take you to unexpected destinations, even when you believe you are on track with something else. You simply have to trust in the process and have faith that your inner voice is leading you there for good reason.

The Royal Family champion many charities, with Mental Health being at the forefront of their work most recently and throughout this pandemic in particular. This is where the mask comes in. I suppose it’s the correlation between the initial NHS portrait I had planned to paint, together with depicting the pandemic lockdown we’re living through as a nation. Despite being Queen of the UK, HRH Queen Elizabeth is travelling through this time as we are. The mask was intended to signify this unity. My decision to paint the Queen immediately came with the notion of her wearing the face mask. I didn’t second-guess it for a moment. It intrigued me and made me question this chapter of our existence. That was the deal-breaker. It was already providing a platform for discussion - albeit solely in my mind at that point!

TNG: The title of the painting refers to the public address the Queen made during lockdown - something she has only done a few times during her reign. What does the Queen mean to you?

EH: Queen Elizabeth ll is a constant to me. Our monarch marks a continuity in our lifetime that I believe is something we should cherish. A positive role model, an anchor for our country and for stabilising us in unity when we face challenging times. She is, ultimately, a superhero of our time.

TNG: How have you found lockdown and the strange period we’ve all been living through?

EH: I have to say that the thought of lockdown was terrifying at the outset. However, I have found the reality somewhat the opposite. Being a creative in lockdown has proved to be enlightening. Time - something most of us tend to struggle to find enough of ordinarily - has become an expanse of personal growth and self improvement, increased creativity (I believe in an act to navigate my way through these times I have clutched to creativity more than ever), and meaningful transformations both as an artist and as a parent. Using this time in lockdown for all the things I have been ’too busy’ for: as someone who already gets up hours before the rest of the household, things I didn’t ever think possible!

Focusing on the positives isn’t something I’ve always been able to do. This period of time in lockdown has taught me that this focus is indeed paramount to making each and every day count. The worries of COVID-19 are very real, but with that comes all the things, the people and places, activities and new opportunities I am grateful for. It’s a reminder that this life is a balancing act. Only we can decide which way the scales will tip.

Leave A Comment